Musings Of A Madman: Sharing Contracts Between APIs and Clients

Note: we decided to model our approach against OctoKit.NET rather than the approach described here. Hence the word Musings in the title. I still thought the idea was interesting enough to document and share.

At Ritter Insurance Marketing, we are in the midst of writing a lot of APIs for our internal and external consumption with the intention of creating less duplication of our data as well as isolating domain functionality. While we are making great strides in achieving our goals, the speed in which we are moving has made each API consumer implement their individual consumer code, contracts, and more. This scenario is less than ideal, and can lead to brittle internal consumption of our APIs.

This post documents a proposed approach to solving the problem while reducing code duplication across our consuming applications.

The Problem

When building an API, you will have several endpoints that expose functionality to your consumers. These consumers expect to receive a payload, which for the scope of this post, I will refer to as a contract. We are attempting to build evolvable APIs, but for our internal applications, we would like to adhere to the latest contract, as not to fall too far behind.

Part Of The Solution

It is a given that most of our applications will be written to work on the ASP.NET and C# technology stack. The homogeny gives us an opportunity to share classes and interfaces between our API and clients. The sharing of contracts will most happen through a Nuget packaging solution, wherein the API maintains these contract artifacts.

My Problem

While I would like to share the structure of my contracts, I do not want to share the implementation used on the API Host. The API Host may choose to implement functionality directly on the local implementation of the contracts that makes no sense in the consuming application. For instance, our host implements a method directly on the contract that builds referential resource links to be passed down with the payload.

My Insane Solution

Note: For this section, I will need you to use your imagination.

Note: For this section, I will need you to use your imagination.

Contracts, by any other name, would smell as sweet or at least be called an interface. These interfaces could help keep a consumer in sync with an API Host, while not leaking implementation details.

// request

public interface IPhoneNumberCreateRequest

{

string Type { get; set; }

string Value { get; set; }

}

// response

public interface ILinks {

public IList<Link> Links { get; set; }

}

public interface IPhoneNumberCreateResponse : ILinks {

int Id { get; set; }

string Type { get; set; }

string Value { get; set; }

}

These interfaces would be passed down via a Nuget package to our consuming applications. You may be asking yourself:

Well, that doesn’t reduce code duplication, does it?

You would be right, not yet. We would have to make some modifications and write a client. Let us look at our modifications to jam pack the contract with helpful information.

[Url("/phone-numbers")]

public interface IPhoneNumberCreateResponse

: ILinks, IResponseFor<IPhoneNumberCreateRequest>

{

int Id { get; set; }

string Type { get; set; }

string Value { get; set; }

}

There is a whole bunch of new information now on our contract.

- The URL template decorates our contract and can be used by our client.

- We have tied the request and response together.

- Our contract describes what the developer has to provide and what they will get for a response.

Now let’s pretend to write a client that understands how to parse these contracts. What might that client look like when being used by a developer?

ApiResult<IPhoneNumberCreateResponse> result =

await Api.ExecuteAsync<IPhoneNumberCreateRequest>(x => {

// x is of type IPhoneNumberCreateRequest

x.Type = "personal";

x.Value = "(555) 555 1234;

});

// implementing our own concrete request class

ApiResult<IPhoneNumberCreateResponse> result =

await Api.ExecuteAsync(new MyLocalPhoneNumberCreateRequest());

The ApiResult class is nothing eventful. Just a wrapper in the case the actual HTTP request fails.

public class ApiResult<T> {

public int StatusCode {get;set;}

public Exception Exception {get;set;}

T Data {get;set;}

}

Ok, now I’m NUTS right?!

How the heck do you use an interface like a concrete implementation?

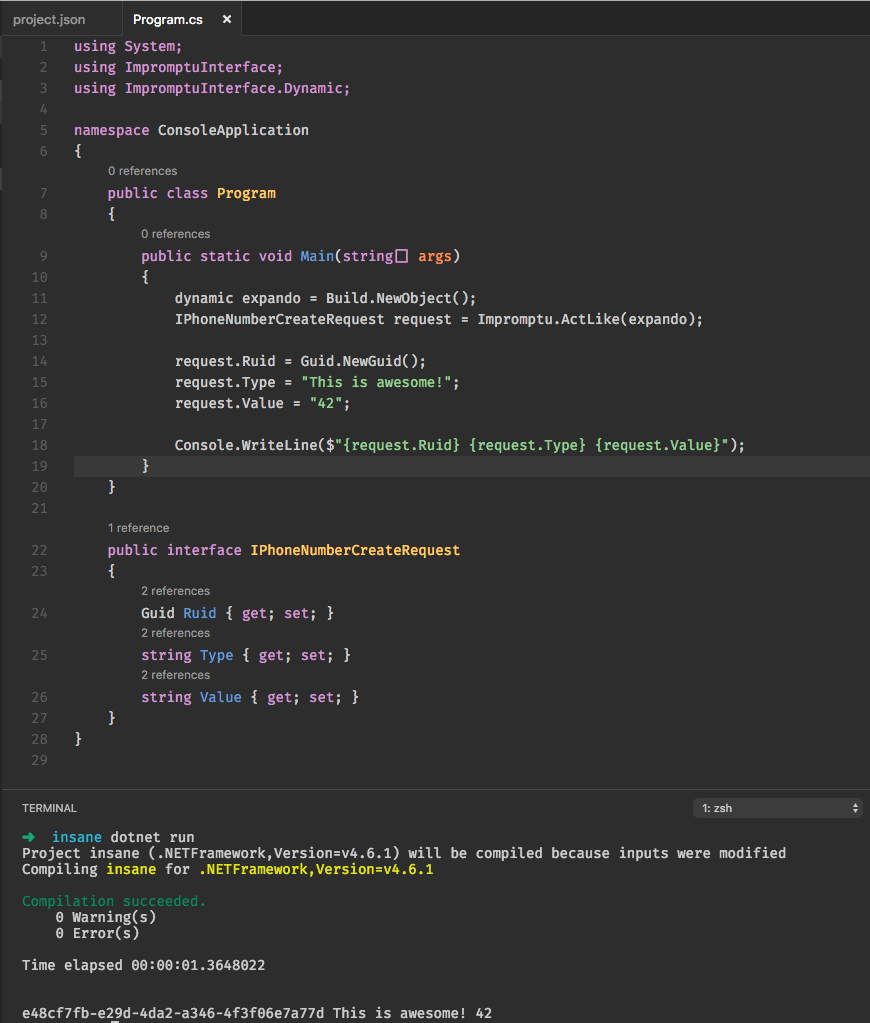

This is where dynamic comes into play. There is a Nuget package named ImpromptuInterface that can create dynamic instances based on interfaces. The advantages are as follows.

- Client code still adheres to a strict contract

- No need to create a local implementation in the consumer app.

- When necessary, You may be able to implement your local implementation of the contract.

Don’t believe me? Here is a screenshot of Impromptu.Interfaces doing its magic.

Conclusion

There are a lot of gray areas here since I haven’t taken the time to implement this approach. I just wanted to document my initial idea so that I didn’t forget about it and to also see what others may think. If anyone does end up applying this method, I’d love to hear from you. I feel like this mental exercise solved my initial problems of keeping clients informed, up to date, being a bit more strict, and keeping code DRY. The concern I may have is the performance of using dynamic objects in an application. Anyways, I hope you enjoyed diving into the mouth of madness with me.